By the early 1780s, my 6th great-grandfather, William Culpepper (1727-1808), had completed his service as a patriot in the Revolutionary War in North Carolina. Records reflect that William served by supplying the soldiers; he was about 50 years old. Soon afterward, he sold his property in North Carolina and, along with his wife and their children, began their migration to Wilkes/Warren County, in eastern Georgia. Their son, Daniel Culpepper Sr. (1750-1819), my 5thgreat-grandfather, was also a North Carolina Revolutionary War patriot. Both William and his son Daniel Sr. are listed on a plaque at the Warren County, Georgia, courthouse honoring Revolutionary War soldiers buried in the County.

When most settlers migrated from North and South Carolina to Georgia, they took along whatever they needed to start their new lives. In a caravan of wagons, they would bring their cows for milk, hogs, chickens, and geese for mattresses and pillows. Some animals were caged, when possible, but the larger animals were herded along the dirt road or path. By the mid 1780’s, William’s family would have built a log home with wood shingles and begun their new life in Georgia.

A few years after they arrived in Georgia and three days before Christmas, on December 22, 1787, William and his wife became charter members of the Church at Williams Creek in Warren County, Georgia (today known as Williams Creek Baptist Church). This would have been the church’s first Christmas service.

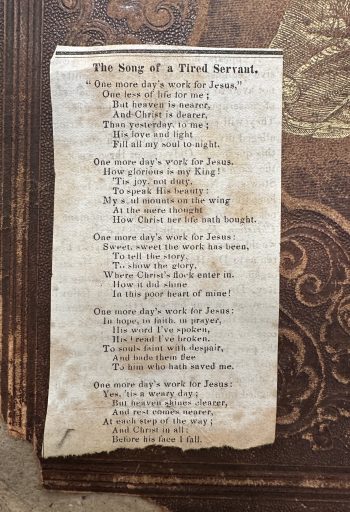

What songs would have been sung that day? Many of the Christmas Carols we sing today (O Little Town of Bethlehem, O Holy Night) were not yet written until the early to middle 1800’s. But there were some carols we love to sing today that became popular in the Middle to late 1700’s. Charles Wesley had written “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” in 1739. Wesley wrote the song in celebration of his new commitment as a Christ follower. The original first line was “Hark the Herald the Welkin (heaven) Sing”. In 1753, George Whitfield, the great preacher and friend of Wesley, changed the first line to what we sing today, “Hark the Herald Angels Sing.” Issac Watts wrote “Joy to the World” in 1719 and was popular towards the end of the 1700’s. The hymn “Amazing Grace” was about 10 years old at the time. Oh, to be a part of the church service that day.

Christmas Day was a few days later, and by this time, William’s children were young adults, and some were married. The matriarch of the family would have led in preparing a simple Christmas meal, cooking it over the open flame and embers in their home’s large fireplace. William or one of his sons would have hunted and killed a wild bird, and if none were found, one or two chickens would have been the main course. To complete the meal, she would have cooked dry beans or possibly green beans, maybe an apple pie (cooked in a Dutch oven, by the fireplace), and bread. Christmas gifts were not a consideration as the family would have been content with the company of their family, an excellent meal, and maybe a part of the day off from their labors. Such was Christmas in pioneer East Georgia in 1787.

Several months ago, Kim and I joined that same Williams Creek Baptist Church. The church still meets on the same property where my grandparents worshiped; the only difference is that we meet in the “new” sanctuary built in 1840. Some of my Culpepper ancestors are buried in marked graves in the cemetery next to the “new building.” I’m convinced that William and his son Daniel Culpepper, along with their families, are buried in the “old cemetery” down the hill in the woods beside Williams Creek. Their graves were probably once marked by field stones or simple wooden crosses, but have now been reclaimed by the nature that the little Boy in the manger created.

This past Sunday, I was honored to play the piano and lead the music for our Christmas Service, marking the 238 years of Christmas services at Williams Creek. Our small congregation shared an excellent Christmas meal after the service because Baptists like to eat.

I look forward to meeting ancestors one day and having a good chat. So, from a grateful great-grandson of two Revolutionary War patriots and Georgia pioneers… Merry Christmas!